notes on an algorithmic deterritorialisation: the Fourth Best view on streaming

Spotify has an algorithmically generated "daily wellness" playlist that's just clips of meditation podcasts cut with generic-sounding lo-fi hip-hop beats and Bressie interludes. Its local coverage is almost entirely dead.

a monolith

I want to revisit an idea I wrote about before – something that I think only got to writing about in a zine which was read by a handful of people. It's the idea of how digital streaming platforms (and, to an extent, social media) act as a force that strips context from music, and how it places careful listening and engagement as a necessary, radical act. This post draws a lot from the work of others, of course - it's an entry point to the discussion - and it will never be the be-all, end-all.

Deterritorialisation is a term from critical theory that is frequently applied to describe the destruction or mutation of context within social relations as a function of late-stage capitalism. I'm nothing like a critical theorist so my use of the term is a bit blunt, but here, I want to apply it to how digital streaming platforms, Spotify being the most studied one, separate music from scenes, genres, community, and push a product that benefits from the transformation of context entirely. Maybe music was the first "gig economy" by name, but it'll be the latest in its new shape.

Spotify openly describes its effect as one that transforms context on the music in its library. "Context is the new genre" is a phrase frequently associated with Spotify's algorithmic and editorial strategy, coined by one of the original developers at the Echo Nest, a company which Spotify absorbed into its data operation. Reverberated by the CEO Daniel Ek, it makes the claim that Spotify can identify the contexts in which people listen to music and meet their needs accordingly; in Ek's words "We need to be able to deliver the right music based on who we are, how we’re feeling and what we’re doing, day-by-day".

Outside of music, Ek spends his Spotify money on investing in military tech.

He's also talked about buying Arsenal: maybe he just thinks they're a weapons manufacturer.

I like to imagine most people who read this have been around the block a few times with the tech industry and know how, in that world, grand narratives are spun long before a solution is viable and companies are propped up by gargantuan amounts of venture capital so that they simply outlast their competition. Take the well-documented example of Uber, which didn't win in the States on the strength of their technology but by pumping venture capital into subsidising low fares and dodging taxi legislation until it priced taxi drivers out of the market. Through their acquisition of the Echo Nest, Spotify gained a powerful analytical engine for music, and they began their redrawing of the lines of genre almost immediately. Thousands upon thousands check their Spotify Wrapped one year and see that their favourite genre has some completely uninterpretable name; "escape room" or "metropopolis".

The academic analyses of Spotify's business model sometimes use the term hybrid gatekeeping - the balance between the human hands that shape design and curatorial decisions combined with the inscrutable machine learning systems that make up what most of us will call "the algorithm". The human hands shape Spotify's home page that tries to limit your choices and funnel users towards a small segment of playlists in the first place, as well as run the platform's myriad editorial playlists - some hyper-specific, some meaninglessly vague.

gates and keys

Since I first put pen to paper on this piece back in October, former Echo Nest employee and former "Lead Data Alchemist" at Spotify, Glenn McDonald, lost his job in a brutal layoff. His work in the public eye took the inscrutable machinery of Spotify and made it open to the rest of the world, in stunning genre maps and data-powered tools that allowed you to discover canonical chains that link artists into scenes. This public work reflects the optimism a younger version of myself might have brought to the digital streaming world. Since he's been cut loose, however, he's been a lot more open about how he sees what his ex-employer has done with his brilliance, and I think he covered the algorithmic arm of the gatekeeper better than I ever could:

Picking unknown artists out of the vast unheard tiers of streaming music is not an act of cultural incubation or stewardship, it's a mechanism of control. There are thousands of bands who sound like this. If you are one of the almost-thousands who are not randomly on my list, there's no action you can take to change this. If any one band ever gets famous this way, and statistically this is bound to happen rarely but eventually, you can be pretty sure we'll hear about it in self-congratulatory press releases that do not feature everyone else left behind. One exception doesn't change the rules. Lottery exposure offers a fleeting illusion of access, but if you didn't build it, you can't sustain it, either. You might hope, if you are in one of these lucky bands that reached me, that millions of not quite metalcore fans also got sets like this on a Friday afternoon, but two Friday afternoons later these bands are still obscure, still isolated. Losing lottery tickets do not make you luckier, but worse, lucking into more listeners this way doesn't give you an audience with any unifying rationale or presence, or a community to join. You can't learn from randomness, you can only hold still and hope it somehow picks you again.

What about the editorial arm? It's surprisingly similar in the end.

Spotify has an editorially "curated" playlist titled "White Noise 10 Hours" with over a million subscribers, no doubt a boon to the randomly selected "artist" in first place, who finds themself with fifty million plays on one track as a result. Their broader editorial process though is largely vibes-based. Playlists have names like "movements." or "Lorem" or "liminal".

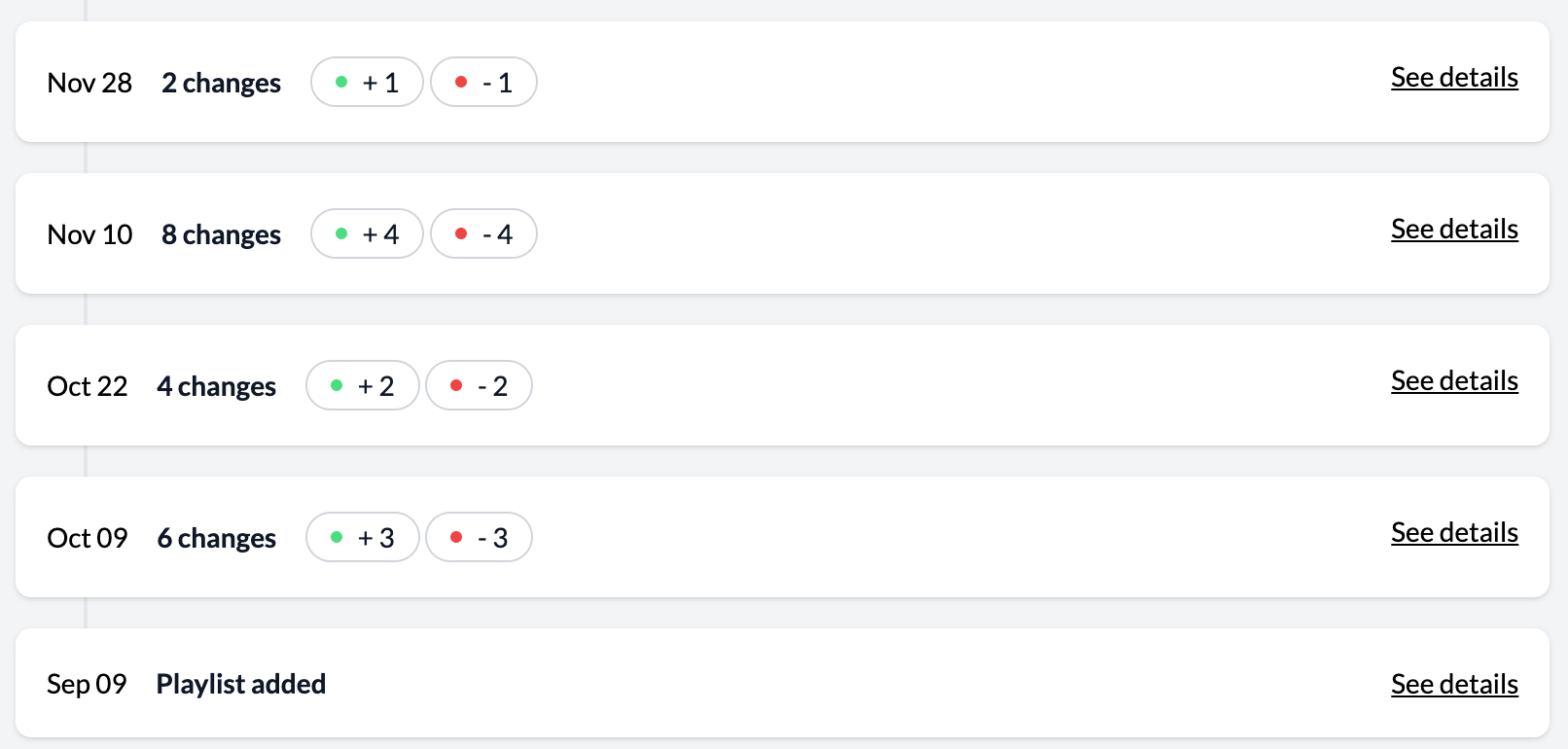

Their coverage of local scenes within their context, at least here, is disposable. Their flagship Irish hip-hop playlist "Ireland 2.0" (fka "The New Éire") has gone without updates in two years at time of writing. "Irish Rap & Drill 2022" wears its age on its sleeve - there is no 2023 edition. The local playlists that do receive attention are painfully non-specific. "A Breath of Fresh Éire" might spend half the year building a map of forward-thinking Irish pop music and then hand the reins over to Niall Horan for some reason. "Alternative Ireland" (fka "An Alternative Éire"), "Irish Dance" (fka "Hands in the Éire"... seriously?) and "Irish Folk" round out the regularly updated lists, although you can be sure there's a handful that get refreshed every St. Patrick's Day.

How do you get on the playlists anyway? At Spotify for Artists Masterclass events the world over, and across their artist-focused documentation, Spotify repeats the same myth:

Whether you’re an established artist or new to the game, Spotify for Artists is the only way to pitch new songs to editors of some of the world’s most followed playlists.

Roc Nation's distribution company Equity says otherwise:

"Our team will make sure your music is heard by the editorial teams at each DSP."

CD Baby's Label Services offers a similar benefit:

"CD Baby Label Services offers you personalized, hands-on support, including editorial pitching."

AWAL too:

"Our global team will seek opportunities to place your music in key playlists."

Millions of artists are told the only way to get editorial support is to line up to be among the uncountably infinite that submit their music through Spotify for Artists every day. Meanwhile, the rest of the industry machinery are quite open about the fact that they still hold keys, and know how directly push buttons that the supposedly liberated "independent artist" probably doesn't have access to.

There isn't a Spotify office in Ireland (although some people love to point out the current global head of playlisting is an Irish man). Nobody from that world is going to see your gig and promote your music as a result. Unless you drag Niall Horan to it so he can do so on his next takeover, I guess.

clockwork smiles

What playlists does Spotify even guide people towards anyway? I found that official "White Noise 10 Hours" flicking through the categories that come up when you try to search for something on the desktop app - that one belonged to "Focus". The categories are a nauseating mix of genres ("pop", "hip-hop"), vague settings ("party", "student"), Spotify jargon ("EQUAL", "Frequency", "GLOW"), and a deeply weird mix of brands ("Netflix", "Disney", "League of Legends"). But the desktop homepage is something that hasn't changed in a while.

The mobile page is changing. It's changing in the way Instagram changes - someone noticed TikTok doing something, so dutifully copy it even if it doesn't make sense to. But I really want you to listen to the music they chose when they announced how that's changing as well.

We announced an all new Spotify experience – the biggest change to the platform since 2013. pic.twitter.com/rOMBFq4W9g

— Daniel Ek (@eldsjal) March 8, 2023

no seriously, you gotta hear the song they used

Back to the desktop. Mixed in with some baffling algorithm picks for me on my home-page are Spotify's seasonal and time-of-day based selections of playlists. These have always seemed off to me - but they're maybe the clearest example of Spotify's functionalist view of music, and what it means to cater to context in their eyes. These playlist suggestions were analysed in a paper by Maria Eriksson and Anna Johansson of Umeå University:

"Music was promoted not only as an aesthetic object but as a performative one. Although playlist descriptions typically included brief characterizations of the music genre they contained, more than half of our collected items pointed to a presumed function of the particular playlist. [...] We suggest that Featured Playlists, through their emphasis on music as a means, may serve as a disciplinary technology that promotes neoliberal subjectivities and attitudes. [...] Spotify suggests chrononormative organizations of everyday life that privilege some lifestyles over others; for example, attending to social relations in the evenings, engaging in intensive and white-collar labor during the day, and upkeeping a romantic life at night time."

I honestly think the most important place to do the deep research on this subject is Liz Pelly's reporting. In her 2019 article Big Mood Machine, she comes to this point:

In Spotify’s world, listening data has become the oil that fuels a monetizable metrics machine, pumping the numbers that lure advertisers to the platform. In a data-driven listening environment, the commodity is no longer music. The commodity is listening. The commodity is users and their moods. The commodity is listening habits as behavioral data.

It isn't useful to Spotify for you to support your local music scenes. Spotify will not be stewards of the archive that artists have given them - they want to be the radio, not the library. It's more useful for Spotify to try to funnel you into these contextless vibes, try to build an analytical profile of your mood and report the findings to advertising networks. Anyone who just uses Spotify as a personal music library and discovery tool knows what it's like for the app to push against them - the introduction of the TikTok style vertical feeds, the library limits, the shuffling around of playlists to distrupt how you file music away, the loud pop-ups to ask you if you'd like to listen to low-effort podcasts that they don't have to pay for instead.

In the article I mentioned above, Pelly quotes a Spotify employee:

“What we’d ultimately like to do is be able to predict people’s behavior through music,” Les Hollander, the Global Head of Audio and Podcast Monetization, said in 2017. “We know that if you’re listening to your chill playlist in the morning, you may be doing yoga, you may be meditating . . . so we’d serve a contextually relevant ad with information and tonality and pace to that particular moment.”

Listen. I don't have to say the next bit. You know what this looks like when ported to an Irish perspective. But fine. Spotify has an algorithmically generated "daily wellness" playlist that's just clips of meditation podcasts cut with generic-sounding lo-fi hip-hop beats and Bressie interludes.

to get back to it

Take Eriksson & Johansson's view of Spotify as imagining perfect neoliberal subjects selecting music for an idealised daily life, take Pelly's experiment in what Spotify would do if you created a fresh account and listened only to the "Coping With Loss" playlist on repeat (desperately try to get you listening to happier music, it turns out), take Spotify's lacklustre contributions to the local level and deliberate disregard of scenes in general in some places, take all the rest - this is what I'm talking about when I describe Spotify as a system of algorithmic deterritorialisation.

Spotify wants to reduce choice, control the narrative, fit neatly into its own idea of how people "use" music. If you as an artist want to even participate in this system, too bad. Maybe your white noise loop or lo-fi beat stands a chance but if you make music in a crowded space and you don't have a label or distributor knocking on the doors for you, or a fanbase that already can expect to see you there, you probably won't make it unless you get the astronomically long-shot of an editor really taking a shine to you. The way that the platform is constructed, the audience that you cultivated off-platform will be ushered away from being lifelong listeners also. Spotify would rather they listen to some podcast about murderers with Reddit accounts or something.

Say you make the astronomically long shot. What then? I've seen artists reticent to have their names on songs they've collaborated on, declining to publish because it's too wild a swing from what algorithms expect from them. I've seen a label with a total focus on Spotify strategy demand an artist to wipe their back catalog and change their artist name because they're afraid that a couple of niche early releases as they figure themselves out will guarantee that an artist is dead-on-arrival. At a talk in Cork a while back I heard a journalist worried about a band they were interviewing using the word "content" to describe their music, which is just a bit grim to most ears.

I've started telling artists there is no point in being on digital streaming platforms unless you can count on thousands of people who'll look for you on day one. The idea that anyone can release music in this formalised way has done the world of damage to a whole generation of artists who would otherwise be focusing on involving themselves in their local contexts and building out from there. The idea that your audience can be the world is an intoxicating myth, but it's a distraction.

the rebuild

The demand is participation, not pity. If the Spotify disaster machine is normal context around music, listening with care is a radical act. It means sharing the music is a radical act. Bringing your friends to gigs is a radical act. Buying the cassette tapes or the tracks on Bandcamp and stuffing them on an iPod is a radical act. Book the rooms. Collaborate. Put others on and have them put you on. Write playlists and put radio shows on. Write about music. Read other people's writing and share it. Buy a tape deck and help people put out music. Create the context. Empower the scene. Call it a grassroots reterritorialisation if you must - a reclamation of the efforts of our communities.

Community resilience is all around you. Féile na Gréine filled every last one of their venues while celebrating the surreal. I had a peek behind the curtain at Cork's new festival River Runs Round, again filling rooms with artists who deserve the audience, building the context and the archive. A mix of DIY types are building Daylight - a member's co-operative cultural space in Dublin - and you can too - claiming inspiration from other still-thriving community institutions like Unit 44, Rebel Reads and Dublin Digital Radio. Little Gem has been playing a blinder over 2023 with their week-in-week-out shows and their day trip to Tipp.

And it's not like it's new, either. The pandemic highlighted the need to builld community spaces while we can, and there's been endless good ideas since. Two years ago as a wave of COVID cleared I travelled to a folk gig down in an former quarry as part of the Signs of Life festival where the organisers handed out film cameras to attendees, with the goal of capturing different perspectives on the gig. I ended up enjoying it enough that I found out about the artist I'm claiming had the Irish album of the year last year.

The enemy is not just Spotify, it's not just digital streaming and it's probably not TikTok. Community resilience also sits in opposition to the economic context that drives people out of Ireland in endless procession. It sits in opposition to small venues closing across the country and the few new arrivals being a useless megaclub or a rake of half-assed mandatory spaces or god fucking forbid another Press Up Group abomination with fake authenticity. They'll bring you the combination Workmans 2 / Stella Cinema / Wagamama in your Granny's house or whatever and put a plaque out front saying it was founded in 859 AD. I don't feel I need to repeat this too loud, it's playing the hits. It's worth reminding ourselves what we're defending - and attacking.